The plan to address active water damage and recover the lost historical archive at Hawara, Fayoum Oasis, Egypt

Contents/Section Links

December 30, 2025 (updated)

Trevor Grassi, Archaeological Rescue Foundation

Excerpts by Louis De Cordier, Mataha Foundation

(Overview below)

The Archaeological Rescue Foundation has been given permission to release a document outlining the master plan for a new Hawara Rescue Project starting now (early 2026)! This plan was written and coordinated by Louis De Cordier, who also led the 2008 Mataha Expedition at the site. Below is a full explanation of the Hawara Labyrinth and its history, with linked reports from all past expeditions, or you can [click here] to skip ahead to the new mission plan document.

Overview

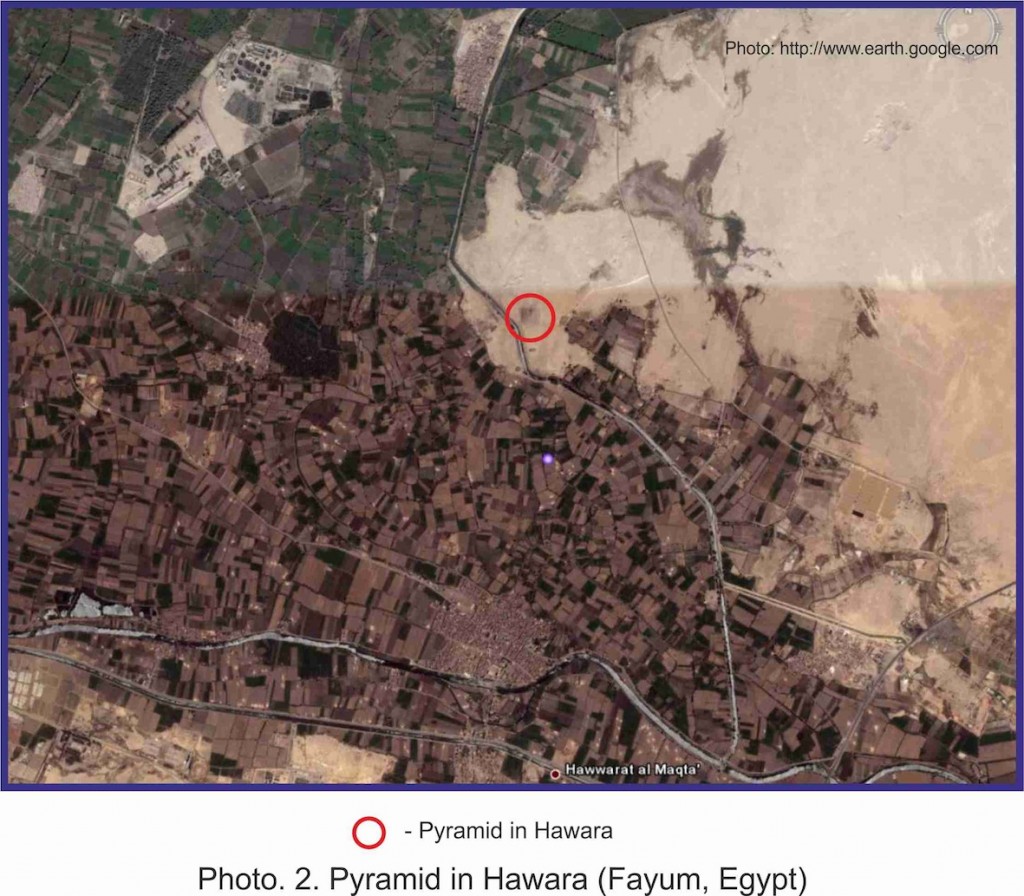

Hawara is an archaeological site situated at the entrance to the Fayoum Oasis, roughly 90 kilometers south of the Giza Plateau. Its primary visible feature is a large mud-brick pyramid, traditionally attributed to Amenemhat III of the Twelfth Dynasty (Middle Kingdom), reigning from around 1860 to 1814 BC. Historical accounts of an enormous complex of underground structures at the site indicate that its true value has remained buried beneath the surface. These sources clearly demonstrate that the so called ‘Hawara Labyrinth’ is one of the most important archaeological sites on the planet.

However, the structure is actively being damaged, primarily by inflowing water from a canal constructed above it in 1820, which keeps many of the chambers constantly flooded. The pyramid itself is also flooded, preventing access to its interior chambers, which were only ever mapped out by Sir William Flinders Petrie in the late Nineteenth Century.

Many of the historical accounts describe the Labyrinth as an endless progression of halls, galleries, palaces, tombs and libraries; impossible to navigate without a guide. Temples to all the Gods of Egypt were also housed within its thousands of chambers on multiple levels descending into the earth. The reports all tend to convey that words fall short of describing the craftsmanship and scale of the structure. They all speak of the art, statues and ‘endless marvels’ that adorned every surface, as if it were, even in ancient times, a museum of sorts; an archive, library or artifact repository intentionally built to preserve knowledge from a far more ancient past.

Today, it remains one of the very few remnants of that lost age of civilization, that we are aware of and capable of accessing.

In this article, and within the referenced supporting documents, we will provide substantial evidence to prove:

- The subterranean complex at Hawara does exist

- It is a repository of artifacts and records of immense cultural significance

- We know how the labyrinth is accessed and could enter it

- Active flooding is causing damage and restricting access to the site

- A thorough analysis of the groundwater has been conducted

- A plan for a permanent solution to the water issue has been established

- With proper funding, we can end the water damage and open the entire labyrinth up for documentation and study

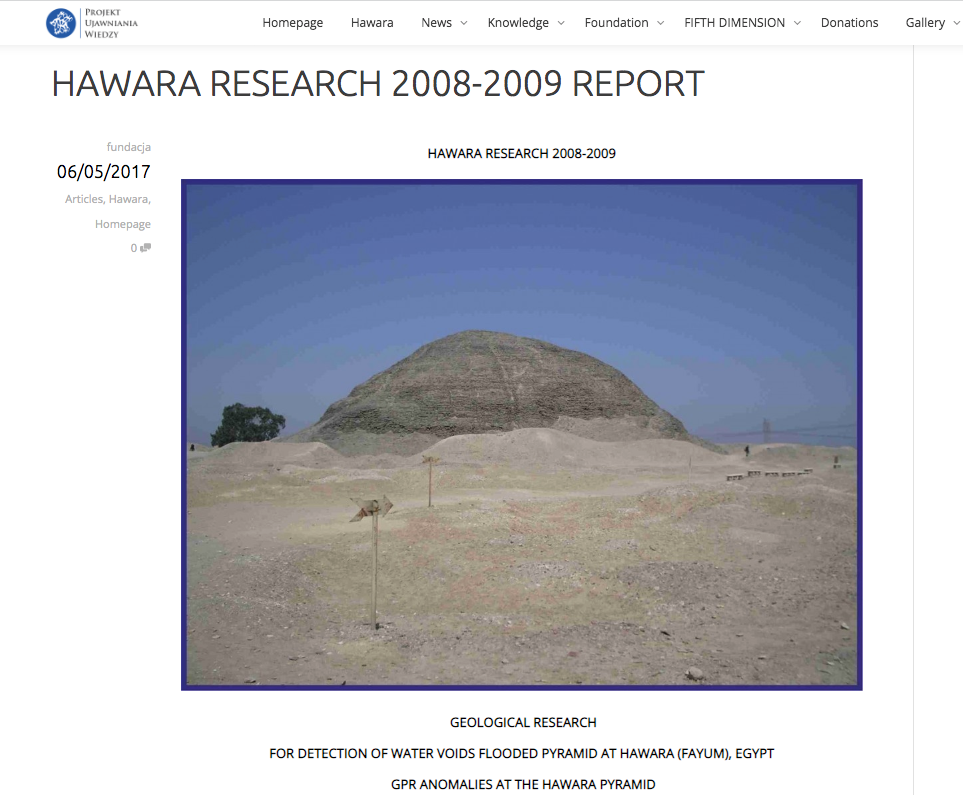

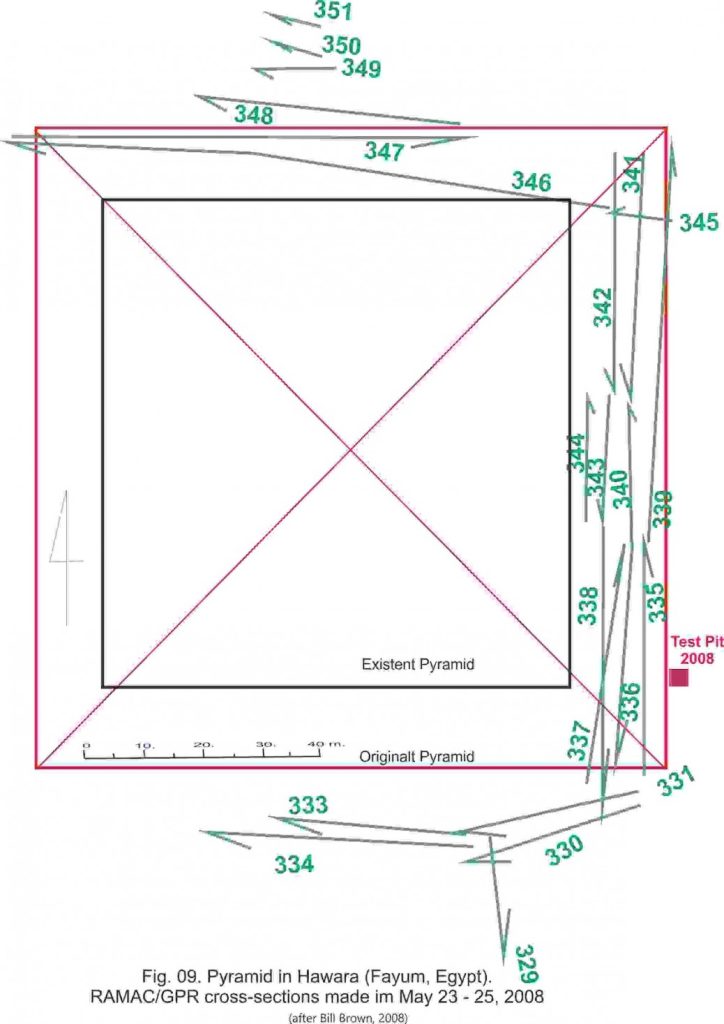

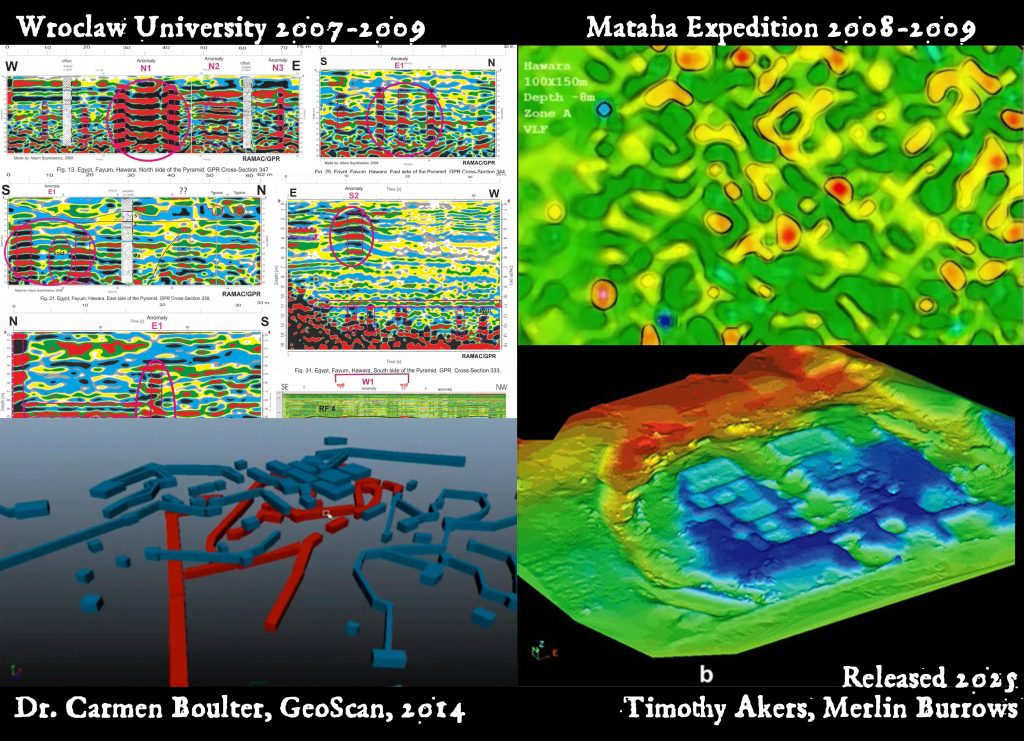

The Archaeological Rescue Foundation is committed to this cause, as the current president of the ARF, William Brown, was on the ground with his wife Lucyna Lobos Brown, leading the very first ground penetrating radar (GPR) scans conducted at the site in 2007-9.

Scan 1: William Brown, Wroclaw University, Cairo University

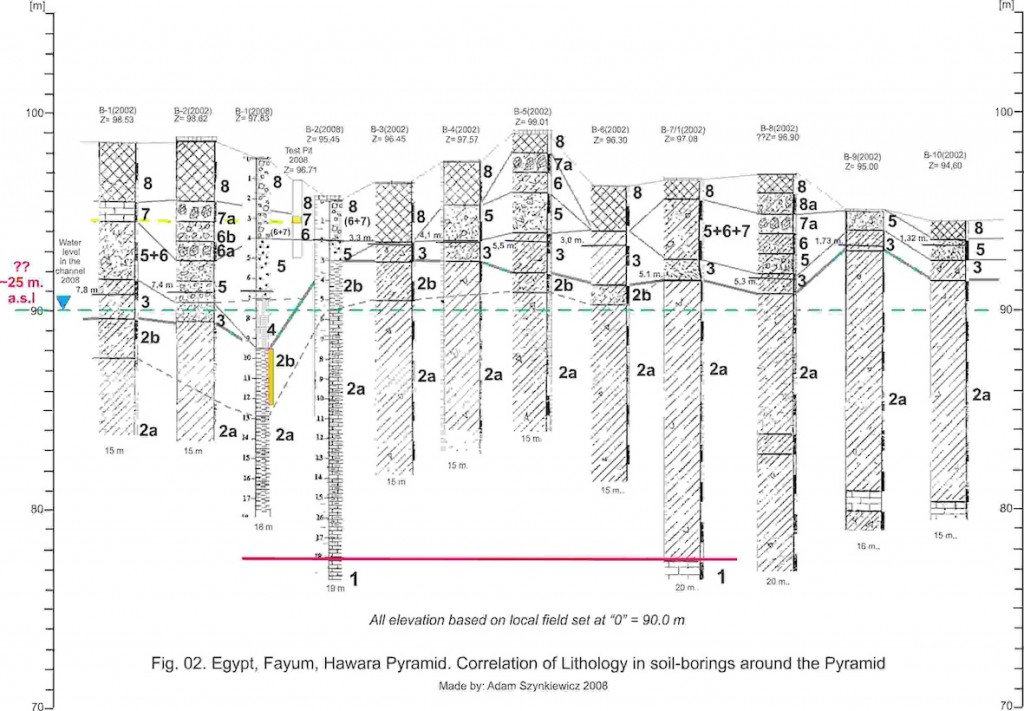

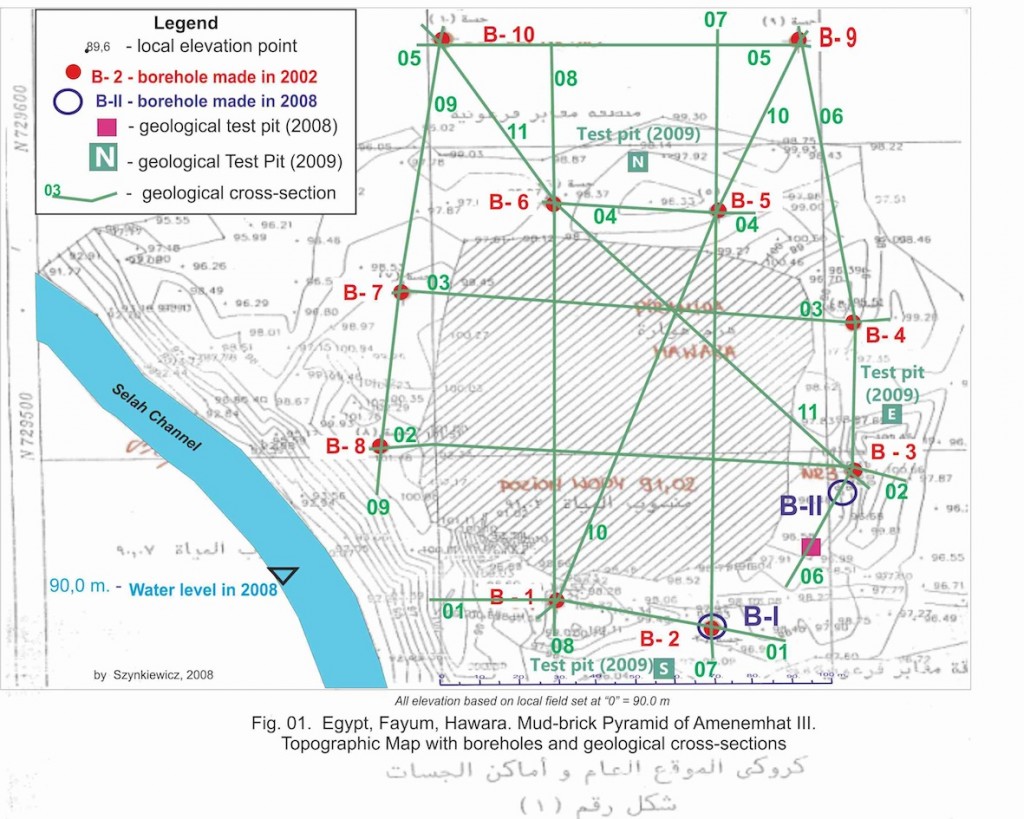

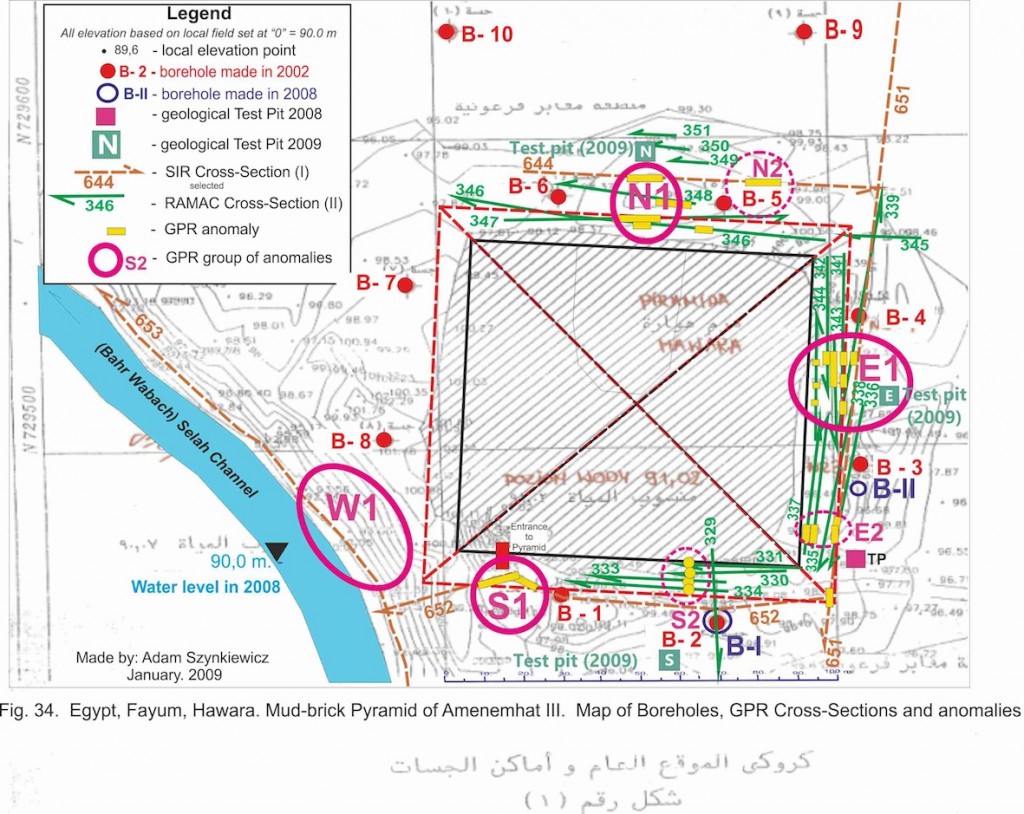

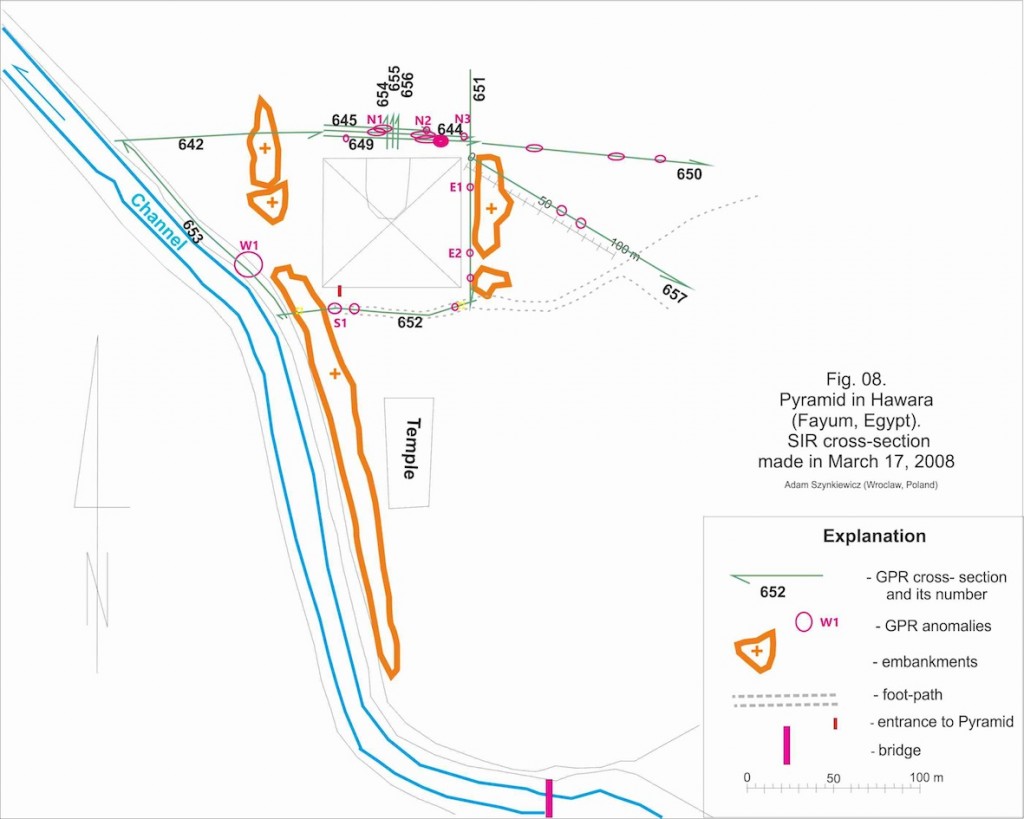

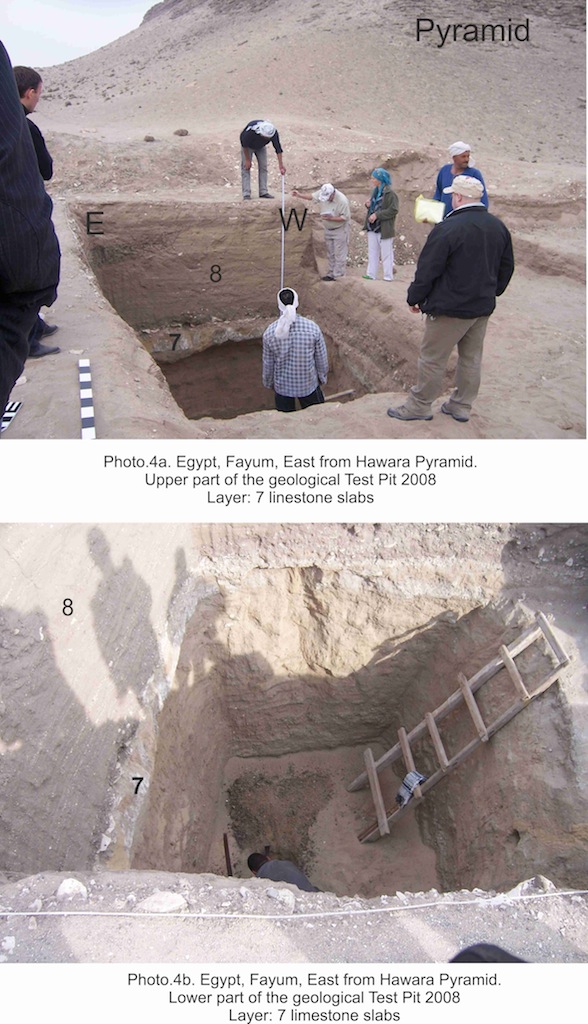

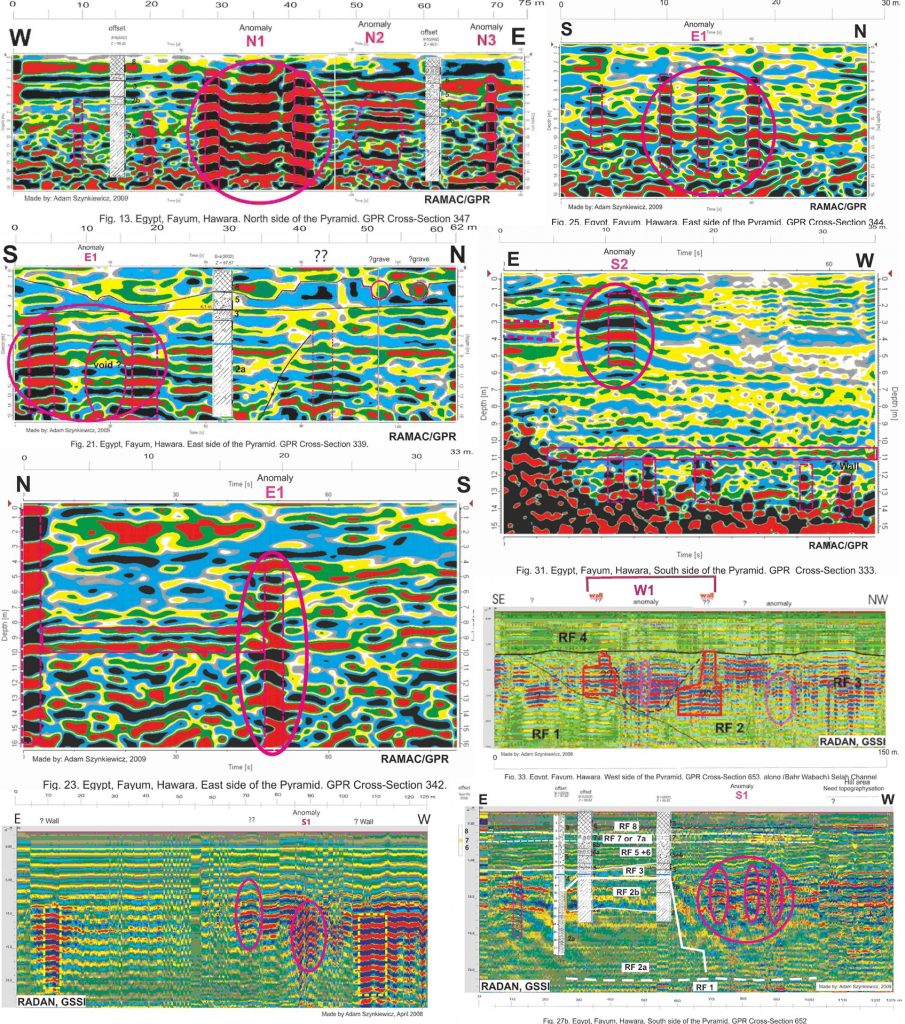

These scans actually revealed the ‘entrance shaft’ below the pyramid that leads down to the Labyrinth. This was a discovery of major importance. He also discovered that the pyramid structure extended deep under the sand, proving it to be much larger than anyone knew, as he found the real corner of it underground. The project was a collaboration between the University of Wroclaw (Poland) and University of Cairo. As a civil engineer with expertise in site plan management, William also conducted the very first analysis of the groundwater by drilling bore holes at strategic points.

The results of this mission are described in the report here:

LINK [HAWARA RESEARCH 2008-2009 REPORT]

LINK [Additional report by Polish group: GPR research around the Hawara pyramid (Fayum, Egypt)]

Bill Brown wrote the very first report proposing ultimate solutions to the groundwater problem, which was presented at a 2009 conference at the University of Cairo, however, another report came out near simultaneously.

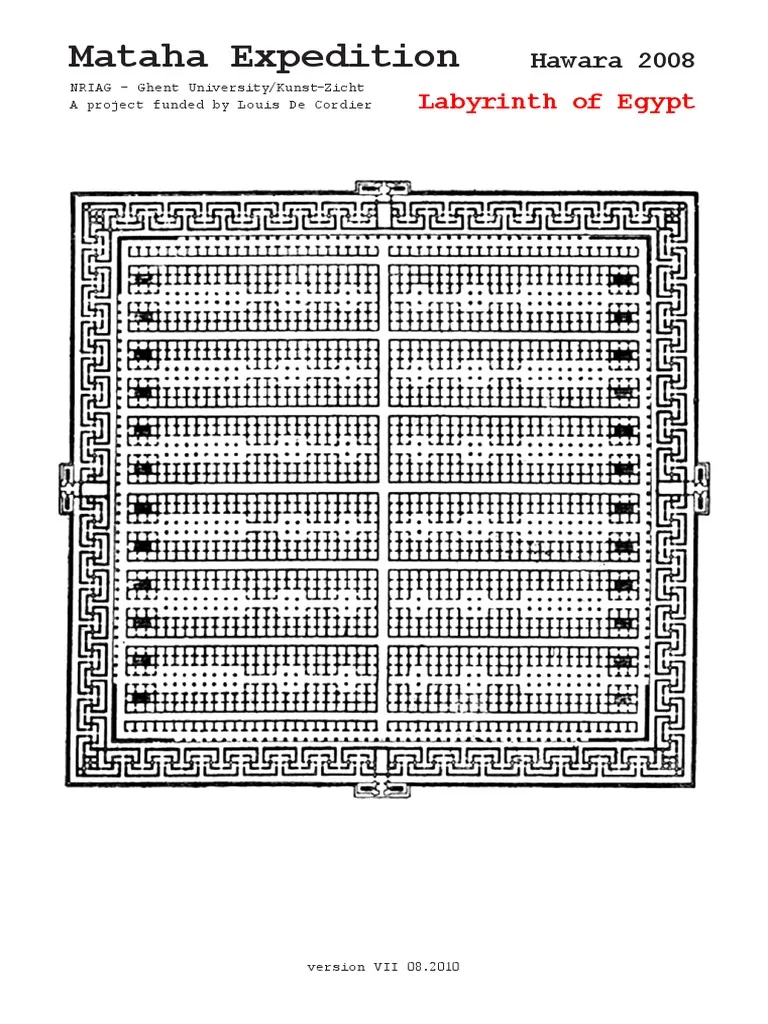

Scan 2: Louis De Cordier, Mataha Expedition

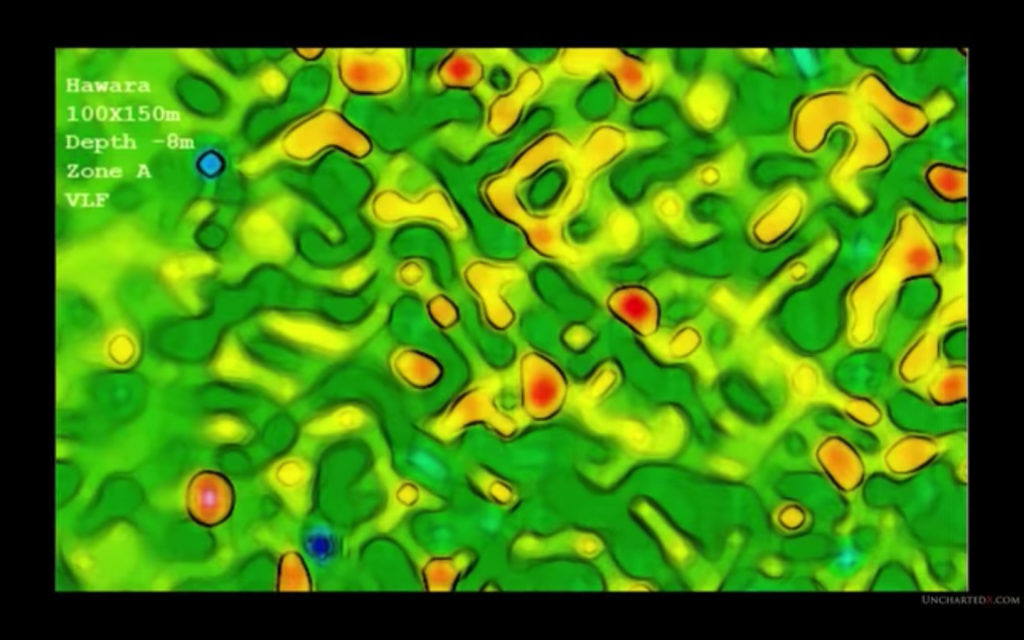

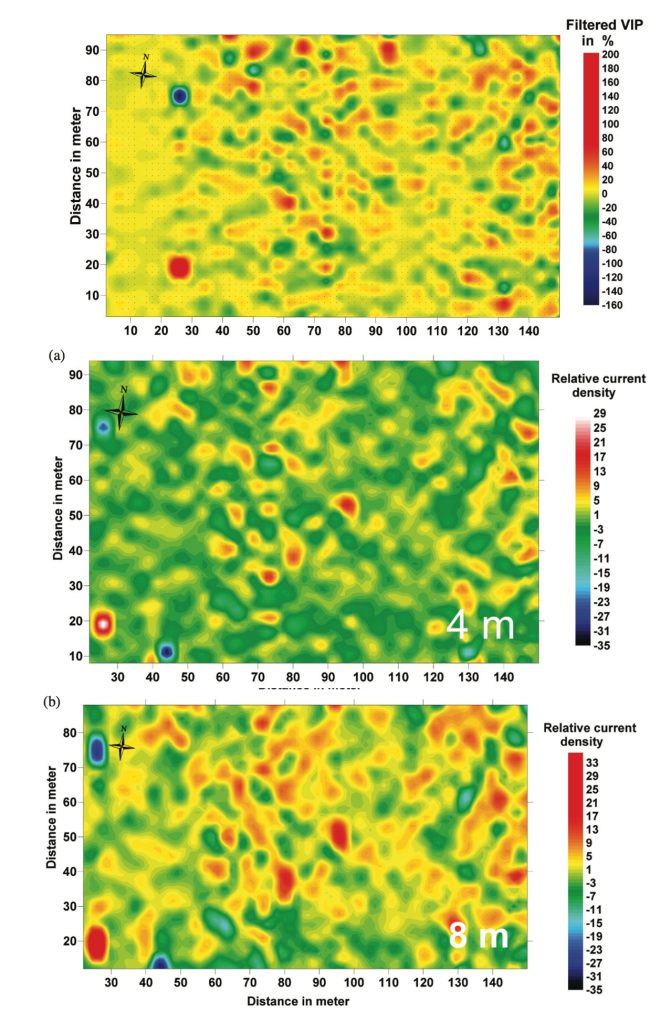

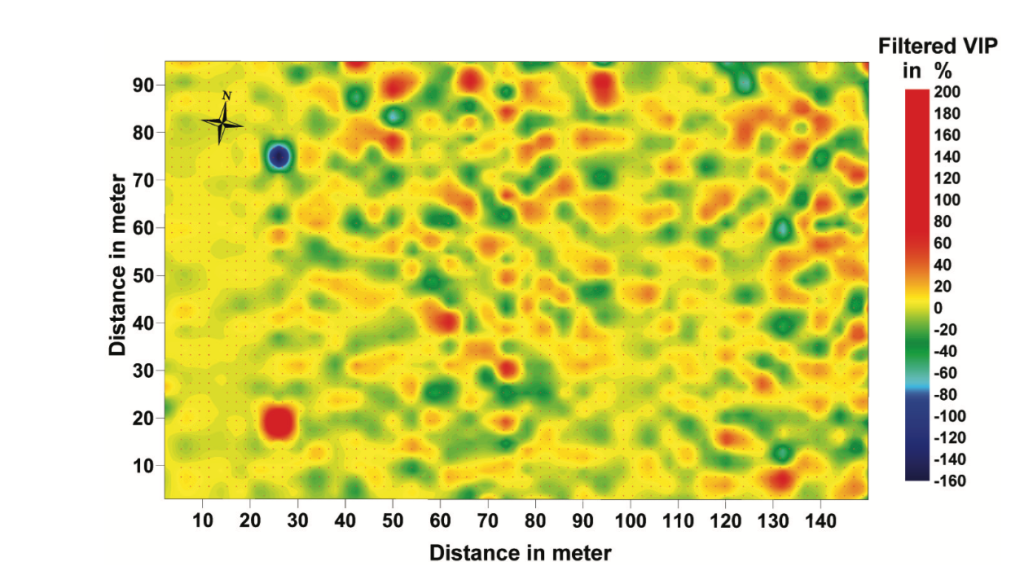

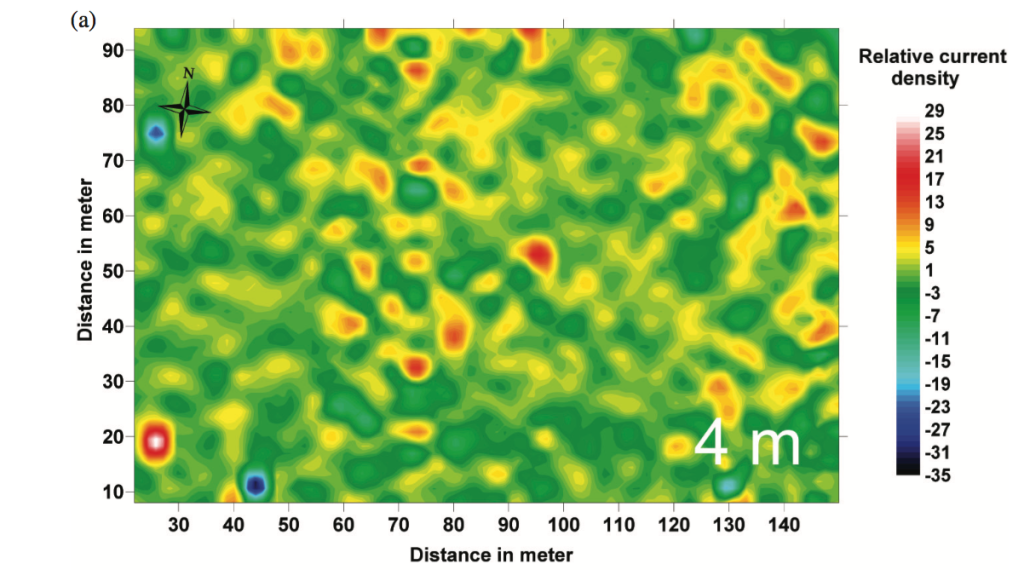

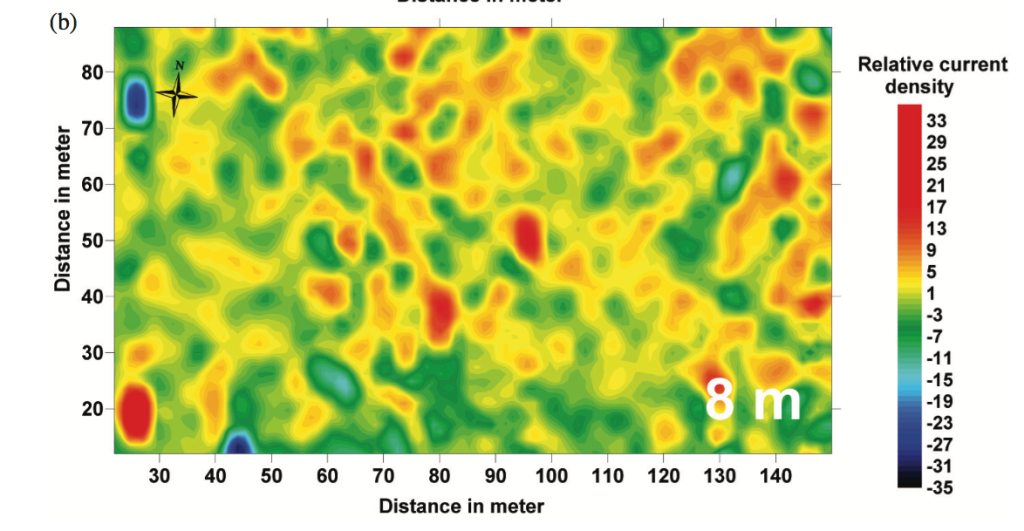

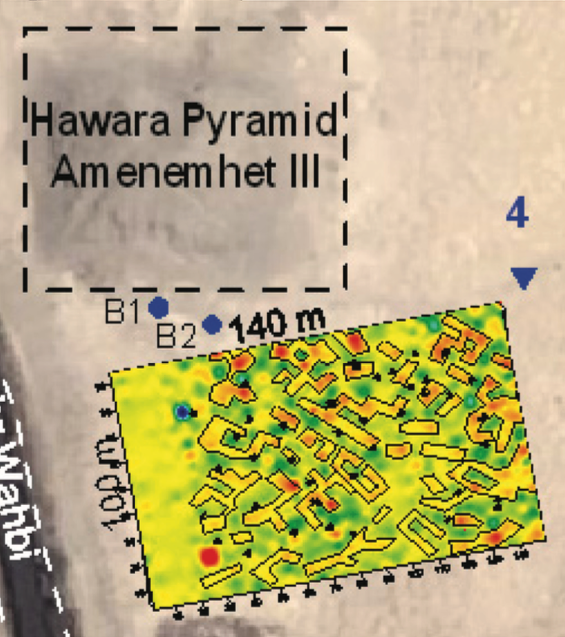

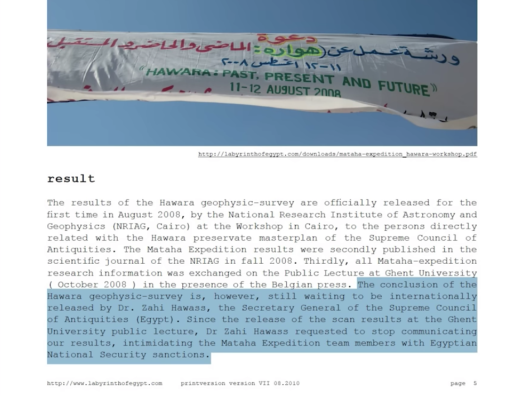

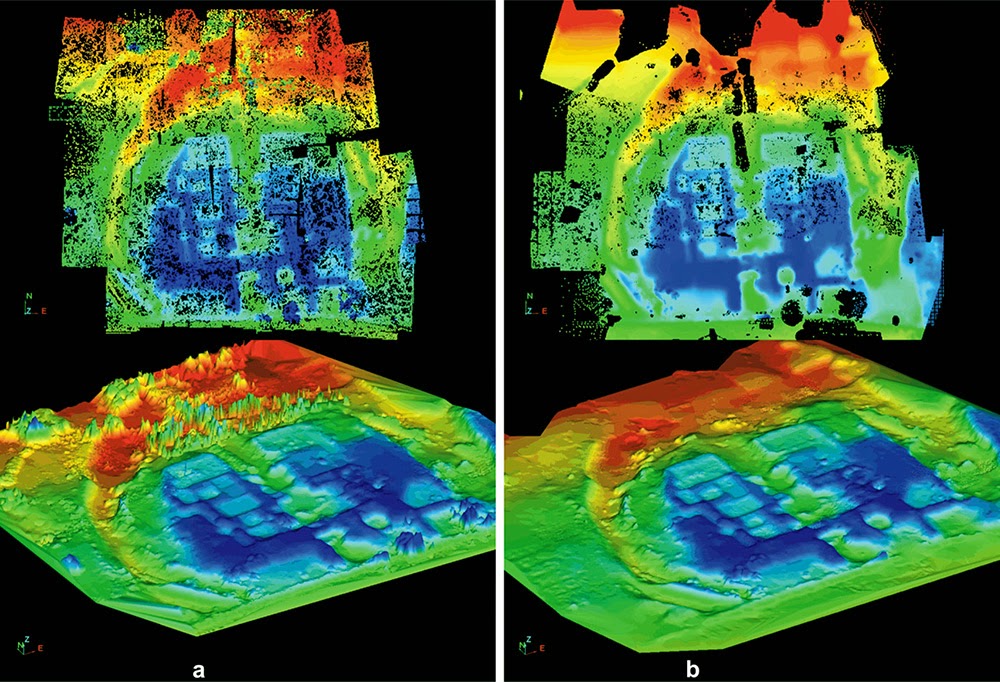

The Mataha Expedition was organized by Louis De Cordier in 2008-9, also conducting GPR scans and using various methods of subsurface sensing to analyze the water problem. Dr. Abbas Mohamed Abbas led the scans with the National Research Institute of Astronomy and Geophysics [NRIAG] (Egypt), in partnership with Ghent University (Belgium), and they showed some of the very first views of the labyrinth structure itself.

An additional report was also released by Dr Abbas and his team very recently, in 2024, with updated information about the water levels:

Louis De Cordier, after facing countless obstructions, is persevering in his efforts to bring together all the right people and proper funding in order establish a preservation and recovery mission at Hawara. Today, the Archaeological Rescue Foundation is partnering with Louis and the MATAHA FOUNDATION [LINK] so as to join our resources and begin the work of saving the priceless monument from any further destruction.

Louis wrote a thorough report covering the history of the labyrinth from Herodotus to Sir William Flinders Petrie, as well as the results of the Mataha Expedition’s scans. His original report is here (and excerpted below):

LINK: [Mataha Expedition Report by Louis De Cordier]

Louis and his team were told not to release this information or tell anyone what they had found. He even wrote that Dr. Zahi Hawass threatened them with national security sanctions, suggesting his knowledge of certain elements within the site that were matters of national importance. Over a decade later, in 2025, Louis would release another major disclosure of the site that seems to explain this hidden element.

Scan 3: Dr. Carmen Boulter, GeoScan

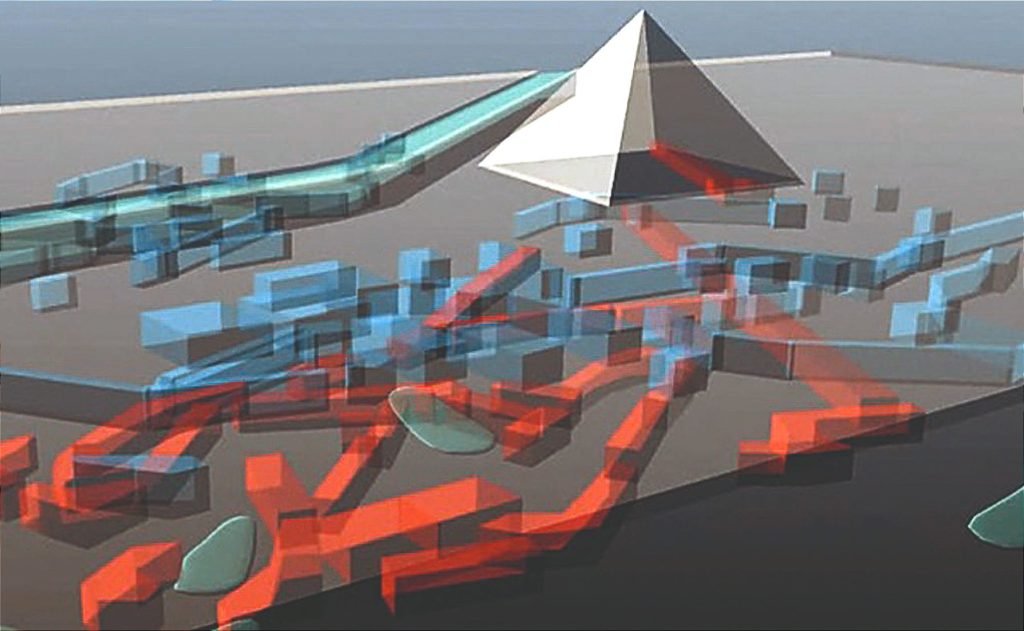

In 2014-2015, there were two additional scanning projects, this time using satellite-based methods. The first was by a company called GeoScan Systems [LINK], principally organized by Dr. Carmen Boulter, with help from Louis De Cordier, Andrew Barker, Klaus Dona and Michael Donnelan. She was able to produce a crude virtual model, extracted from the satellite data, showing two levels of the labyrinth that were separated. The blue level above was described as flooded, while the red level below was not.

[LINK] GeoScan Systems technology explained

Dr. Boulter sadly passed in 2022, but she is remembered as we aim to finish the task that she and many others contributed to. William also corresponded with her while she was presenting her research on Hawara, meeting at the International Scientific Pyramids Conference. This material would have likely been included in the series that she was nearly ready to release when she died. This would have been a follow up to her original docu-series, The Pyramid Code [LINK].

Mark Carlotto, however, has compiled two papers about some of the satellite based SAR sensing, that include some information about Carmen’s work.

LINK [Space-based Ground Penetrating Imaging of the Ancient Labyrinth at Hawara]

Scan 4: Merlin Burrows, Timothy Akers

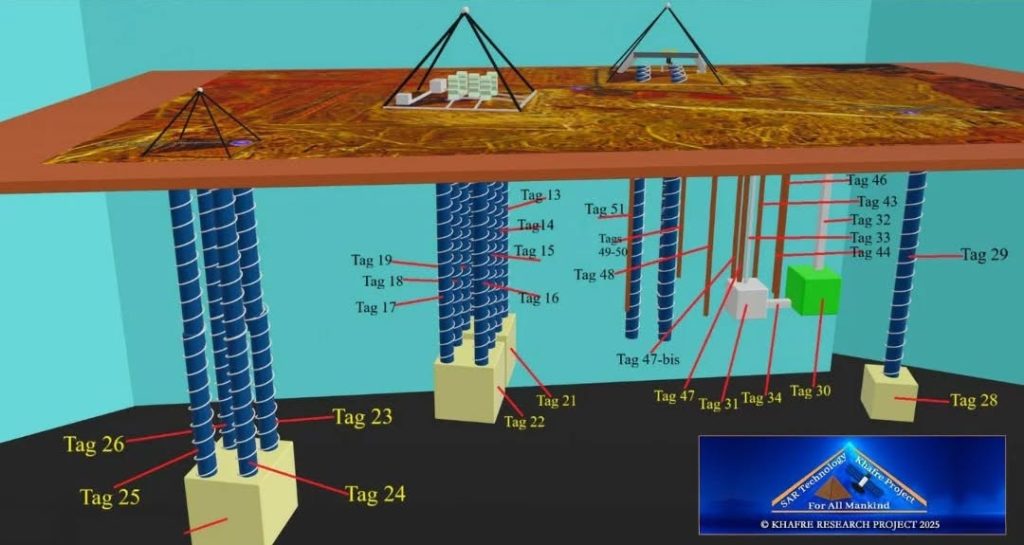

Shortly after this project, another scan was carried out, in the hopes of seeing a more detailed picture of the structure. This was led by Timothy Akers, with a company that later came to be called MerlinBurrows [LINK]. Louis De Cordier was also involved in this operation, and along with everyone else present, signed a 10 year non disclosure agreement regarding the scan results. This was, at least in part, due to the intimidation efforts by Hawass, to silence the Mataha Expedition, and also in part, due to the extreme sensitivity of what was discovered. It was deemed by all to be safer not to release the information at that time.

They could not have imagined in 2015, that in 2025, SAR scans of the Giza Plateau would be released showing structures over a kilometer in scale. The discovery of the Khafre Research Project kindled the world’s interest in satellite archaeology and lost halls of records, in perfect time for Louis to release the extraordinary discoveries he had to keep bottled up for a decade.

The disclosure of the new Hawara scans amplified a viral wave of interest when Louis revealed the whole story in a two part article:

LINK [The Merlin Burrows Scans I]

LINK [The Merlin Burrows Scans II]

So to date, four separate scanning missions have not only all confirmed that the structure still exists underground, but the scans have given us many additional clues that all confirm indications from antiquity; that the labyrinth was vast, complex and full of artifacts that could change everything we know about human history.

Furthermore, the Archaeological Rescue Foundation has brought this site to the attention of Dr. Filippo Biondi of the Khafre Research Project [LINK] and he has agreed to scan Hawara once his work at Giza is complete, estimated by the Summer of 2026. This will be the fifth scanning project at Hawara, and at least one member of our current extended team was present at every one.

As outlined by Louis in his two part article, the new scans contained much more information than the untrained eye can deduce by looking at the image. The greater revelations come from the explanations given by Timothy Akers before he sadly also passed.

His description includes countless discoveries of immense importance, including a massive domed structure roughly equivalent in scale to Hagia Sofia in Istanbul.

They also found two, large wooden boats, near the surface, in the style of the Khufu Solar Boat found at Giza.

Khufu’s Solar Boat was one of several that were discovered in pits around the pyramids at Giza. They were carefully disassembled, piece by piece, and stored to be preserved for thousands of years. They are considered to be some of the earliest organic artifacts on Earth, as wood generally decays, but since they were stored in the dry desert sand, they remained perfectly preserved, as if mummified.

However, the two boats that Timothy Akers describes, are fully assembled in place. He shows them on the western end of the complex, and very close to the surface, meaning they are in the flood zone of the canal and must be rescued from water damage as soon as possible.

Tim Akers goes on to describe an endless complex of chambers around an enormous central gallery (at least 40 x 100 meters), much like the atrium of a shopping mall, opening up to balconies on multiple levels. He saw patterns of structures at 40, 60, 80 and 100 meter depths.

More intriguing still, he detected a centerpiece in the middle of the grand central gallery, that he described as a 40 meter, free standing, metallic object, though showing a specific material signature unlike any he had detected in his entire career. We do not know what this object is, but it has captured the world’s imagination, and today, more than ever before, we are finally coming to recognize the level of impact the Hawara archive could have, if it were to be accessed and documented.

There was no doubt in his mind that he was looking at the very object that the whole labyrinth was originally built to conceal. This object, made of an unknown metal and nearly spanning half a football field in length, was clearly the centerpiece of the central atrium, and of the entire complex.

While this material is all presented in his article, Louis has also explained the story in an interview with William Brown and myself (Trevor Grassi). We explain the need for action to be taken, and describe a plan for what can be done. To date, this is the only interview with Louis on this subject.

Rekindling the flames of the Mataha Expedition, Louis has worked tirelessly in 2025 to gather the required resources, people, equipment and funding to pull together the final mission for the preservation, restoration, documentation and recovery of Hawara’s untold cultural treasures, and the Archaeological Rescue Foundation is proud to support him in this noble endeavor.

Plan and cost

Eventually, the entire canal must be rerouted around the entire site, and initially, it must at least be patched with cement and grasses must be planted in the northern areas, as their root structures will divert much of the water flowing in from the north. Without the constant inflow, the water can be drained and the structures entered. Many chambers will need excavation of sand or mud, which will require a large a digging team for many seasons, plus archaeological professionals and security.

Once we can enter the structures, without touching a single item, it will be possible to create a perfect photogrammetric model of the entire complex exactly it is, using precise equipment to establish measurements of each chamber and 360 degree cameras to map their surfaces.

The cost will be well into the millions, and the project will last for many years to come, but the voluminous body of evidence promises results of priceless value, that stand to benefit all of humanity, and especially Egypt. A discovery of this magnitude; showing the whole world this 40 meter object and the 3,000 chambers (according to Herodotus) that surround it, all decorated in fine stones, art and records, could potentially double the scale of the tourism industry for the whole country, and all Egyptians would benefit. It will also take into account the water needs of the local farmers, as lowering the water table too far could affect local agriculture.

A comprehensive, step by step mission plan for the project has been written by Louis, detailing every single concern that must addressed, and the Archaeological Rescue Foundation is excited to announce that we have been given permission to release this document, as of February 9, 2026.

(Click link above to view full size.)

According to Herodotus, who was often called the ‘Father of History’, the Hawara Labyrinth is essentially the greatest architectural achievement in all of history; the single greatest ‘wonder of the ancient world’. He described it as superior to the Giza Pyramids, which were themselves, superior to all the works of the Greeks.

(Extended quotes from Herodotus and other eyewitnesses of the Labyrinth can be found below, describing its unparalleled craftsmanship, precision and beauty, as well as its colossal scale.)

Keep in mind, the site is not only at risk, but it is actively being damaged by flooding.

We believe that no price can be placed on a treasure of such value. It is simply our duty, as human beings, to protect and preserve this monument by any means required, as it represents the highest achievements of humanity’s collective cultural heritage. It it also the heritage of future generations, who deserve the right to witness it as much as we do today. Entering the lost labyrinth may come to be remembered in history as another ‘small step for man, and giant leap for mankind’.

Donations towards this project, from the smallest to the greatest, will help us to ensure the lost labyrinth is preserved and shared with the world. The Archaeological Rescue Foundation now aims to raise funding that can support Louis and the Hawara Mission with grants for years to come, to ensure that this long term project can be carried out without interruption. To become a principal funder, please feel free to contact info@archaeologicalrescue.org for more information, or make a (tax-deductible) donation here:

SUPPORT THE HAWARA RESTORATION

Cultural Significance

The following compilation is excerpted (with permission) from Louis De Cordier’s Mataha Expedition report, linked above. Additionally, Ben Van Kerkwyk of UnchartedX [LINK] has compiled a very informative video presentation of the historical accounts and excavations of Hawara here:

…

Historic documentation of the subterranean structure begins with Herodotus (ca. 484-430 BC) who wrote the following in Histories, Book II, p 148-9:

Moreover they (the 12 kings) resolved to join all together and leave a memorial of themselves; and having so resolved they caused to be made a labyrinth, situated a little above the lake of Moiris and nearly opposite to that which is called the City of Crocodiles. This I saw myself, and I found it greater than words can say. For if one should put together and reckon up all the buildings and all the great works produced by the Hellenes, they would prove to be inferior in labour and expense to this labyrinth, though it is true that both the temple at Ephesos and that at Samos are works worthy of note. The pyramids also were greater than words can say, and each one of them is equal to many works of the Hellenes, great as they may be; but the labyrinth surpasses even the pyramids. It has twelve courts covered in, with gates facing one another, six upon the North side and six upon the South, joining on one to another, and the same wall surrounds them all outside; and there are in it two kinds of chambers, the one kind below the ground and the other above upon these, three thousand in number, of each kind fifteen hundred. The upper set of chambers we ourselves saw, going through them, and we tell of them having looked upon them with our own eyes; but the chambers under ground we heard about only; for the Egyptians who had charge of them were not willing on any account to show them, saying that here were the sepulchres of the kings who had first built this labyrinth and of the sacred crocodiles. Accordingly we speak of the chambers below by what we received from hearsay, while those above we saw ourselves and found them to be works of more than human greatness. For the passages through the chambers, and the goings this way and that way through the courts, which were admirably adorned, afforded endless matter for marvel, as we went through from a court to the chambers beyond it, and from the chambers to colonnades, and from the colonnades to other rooms, and then from the chambers again to other courts. Over the whole of these is a roof made of stone like the walls; and the walls are covered with figures carved upon them, each court being surrounded with pillars of white stone fitted together most perfectly; and at the end of the labyrinth, by the corner of it, there is a pyramid of forty fathoms, upon which large figures are carved, and to this there is a way made under ground.

Such is this labyrinth; but a cause for marvel even greater than this is afforded by the lake, which is called the lake of Moiris, along the side of which this labyrinth is built…

Diodorus Siculus, in the First Century BC wrote in his History, Book I, 61.1-2 and 66.3-6:

“When the king died the government was recovered by Egyptians and they appointed a native king Mendes, whom some call Mares. Although he was responsible for no military achievements whatsoever, he did build himself what is called the Labyrinth as a tomb, an edifice which is wonderful not so much for its size as for the inimitable skill with which it was build; for once in, it is impossible to find one’s way out again without difficulty, unless one lights upon a guide who is perfectly acquainted with it. It is even said by some that Daedalus crossed over to Egypt and, in wonder at the skill shown in the building, built for Minos, King of Crete, a labyrinth like that in Egypt, in which, so the tales goes, the creature called the Minotaur was kept. Be that as it may, the Cretan Labyrinth has completely disappeared, either through the destruction wrought by some ruler or through the ravages of time; but the Egyptian Labyrinth remains absolutely perfect in its entire construction down to my time.

And seized with enthusiasm for this enterprise they strove eagerly to surpass all their predecessors in the seize of their building. For they chose a site beside the channel leading into Lake Moeris in Libya and there constructed their tomb of the finest stone, laying down an oblong as the shape and a stade as the size of each side, while in respect of carving and other works of craftsmanship they left no room for their successors to surpass them. For, when one had entered the sacred enclosure, one found a temple surrounded by columns, 40 to each side, and this building had a roof made of a single stone, carved with panels and richly adorned with excellent paintings. It contained memorials of the homeland of each of the kings as well as of the temples and sacrifices carried out in it, all skillfully worked in paintings of the greatest beauty. Generally it is said that the king conceived their tomb on such an expensive and prodigious scale that if they had not been deposed before its completion, they would not have been able to give their successors any opportunity to surpass them in architectural feats.”

Strabo (ca. 64 BC- 19 CE) included in his Geography, Book 17; 1, 3, 37, and 42:

“… the total number of nomes was equal to the number of the courts in the Labyrinth; these are fewer than 30. In addition to these things there is the edifice of the Labyrinth which is a building quite equal to the Pyramids and nearby the tomb of the king who built the Labyrinth. There is at the point where one first enters the channel, about 30 or 40 stades along the way, a flat trapezium-shaped site which contains both a village and a great palace made up of many palaces equal in number to that of the nomes in former times; for such is the number of peristyle courts which lie contiguous with one another, all in one row and backing on one wall, as though one had a long wall with the courts lying before it, and the passages into the courts lie opposite the wall. Before the entrances there lie what might be called hidden chambers which are long and many in number and have paths running through one another which twist and turn, so that no one can enter or leave any court without a guide. And the wonder of it is the roofs of each chambers are made of single stones and the width of the hidden chambers is spanned in the same way by monolithic beams of outstanding size; for nowhere is wood or any other material included. And if one mounts onto the roof, at no great height because the building has only one storey, it is possible to get a view of a plain of masonry made of such stones, and, if one drops back down from there into the courts, it is possible to see them lying there in row each supported be 27 monolithic pillars; the walls too are made up in stones of no less a size.

At the end of this building, which occupies anarea of more than a stade, stands the tomb, a pyramid on a oblong base, each side about 4 “plethra” in length and the height about the same; the name of the man buried there was Imandes. The reason for making the courts so many is said to be the fact that it was customary for all nomes to gather there according to rank with their own priests and priestesses, for the purpose of sacrifice, divine- offering, and judgement on the most important matters. And each of the nomes was lodged in the court appointed to it. And above this city stands Abydos, in which there is the Memnonium, a palace wonderfully constructed of massive stonework in the same way as we have said the Labyrinth was built, though the Memnonium differs in being simple in structure.”

Pliny the Elder (23-79 AD) wrote in Natural History, Book 36, p 84-89:

“Let us speak also of labyrinths, quite the most extraordinary works on which men have spent their money, but not, as may be thought, figments of the imagination. There still exists even now in Egypt in the Heracleopolite Nome the one which was built first, according to tradition 3,600 years ago by king Petesuchis or Tithois, though Herodotus ascribes the whole work to Twelve Kings and Psammetichus, the latest of them. Various reasons are given for building it. Demoteles claims that it was the palace of Moteris, Lyceas the tomb of Moeris, but the majority of writers take the view that it was build as a temple to the Sun, and this is generally accepted. At any rate, that Daedalus used this as the model for the Labyrinth which he built in Crete is beyond doubt, but it is equally clear that he imitated only 100th part of it which contains twisting paths and passages which advance and retreat- all impossible to negotiate. The reason for this is not that within a small compass it involves one in mile upon of walking, as we see in tessellated floors or the displays given by boys on the Campus, but that frequently doors are buried in it to beguile the visitor into going forward and then force him to return into the same winding paths. This was the second to be built after the Egyptian Labyrinth, the third being in Lemnos and the fourth in Italy, all roofed with vaults of polished stone, though the Egyptian specimen, to my considerable astonishment, has its entrance and columns made of Parian marble, while the rest is of Aswan granite, such masses being put together as time itself cannot dissolve even with the help of the Heracleopolitans; for they have regarded the building with extraordinary hatred.

It would be impossible to describe in detail the layout of that building and its individual parts, since it is divided into regions and administrative districts which are called nomes, each of the 21 nomes giving its names to one of the houses. A further reason is the fact that it also contains temples of all the gods of Egypt while, in addition, Nemesis placed in the building’s 40 chapels many pyramids of 40 ells each covering an area of 6 arourae with their base. Men are already weary with travelling when they reach that bewildering maze of paths; indeed, there are also lofty upper rooms reached by ramps and porticoes from which one descends on stairways which have 90 steps each; inside are columns of imperial porphyry, images of the gods, statues of kings and representations of monsters. Certain of the halls are arranged in such way that as one throws open the door there arises within a fearful noise of thunder; moreover one passes through most of them in darkness. There are again other massive buildings outside the wall of the Labyrinth; they call them “the Wing”. Then there are other subterranean chambers made by excavating galleries in the soil. One person only has done any repairs there-and they were few in number. He was Chaermon, the eunoch of king Necthebis, 500 years before Alexander the Great. A tradition is also current that he supported the roofs with beams of acacia wood boiled in oil, until squared stones could be raised up into the vaults.”

Pomponius Mela (First Century CE), in Chorographia wrote:

Pomponius Mela (1st century CE): One passage in his chorographia, Book I, 9, 56.

“The building of Psammetich, the Labyrinth, includes within the circuit of one unbroken wall 1000 houses and 12 palaces, and is built of marble as well as being roofed with the same material. It has one descending way into it, and contains within almost innumerable paths, which have many convolutions twisting hither and thither. These paths, however, cause great perplexity both because of their continual winding and because of their porticoes which often reverse their direction, continually running through one circle after another and continually turning and retracing their steps as far as they have gone forwards with the result that the Labyrinth is fraught with confusion by reason of its perpetual meandering, though it is possible to extricate oneself.”

History of Expeditions

(The following is an additional excerpt from the Mataha Expedition Report, by Louis De Cordier)

Mataha Expedition – Labyrinth of Egypt – http://www.matahafoundation.org

papyri

The village Hw.t-wr.t/Αὑῆρις (= great temple) is attested 119 times in 62 documents between 292 BC and 141 CE. The concentration of documents in the 1st century BCE is due to the Hawara undertakers archives. The Egyptian labyrinth (Λαβύρινθος) appears 18 times in 16 papyri between 258 BCE and the reign of Hadrian (117-138 CE). All texts but one are Ptolemaic. Though the names Hw.t-wr.t/Αὑῆρις and Λαβύρινθος disappear early from our records, archaeological finds show that the site was continuously occupied up to the 7th century CE. The Egyptian name Hw.t-wr.t corresponds to Greek Αὑῆριςin several bilingual documents, e.g. P.Hawara Lüdd. III (233 BCE), P.Ashm. I 14 and 15 (72/71 BCE) and P.Ashm. I 16 (69/68 BCE). The aspiration at the beginning of the word shows in the phi in ̔Αγουήρεως τῆς ̔Ηρακ[λείδου μερίδος] (where ̔Αγουήρεως stands for Αὑῆρις) in SB XIV 11303. Greek ἁ for Egyptian hw.t is found in other toponyms as well (Clarysse-Quaegebeur 1982, p.78)

early explorers

A structure which evoked so much wonder and admiration in ancient times hardly failed arouse the curiosity of later generations, but no serious attempts to locate it seem to have been made by Europeans until several centuries later. It was then far too late to observe any of its glories, for it disappeared in Roman times, and a village sprang up on its site, largely constructed from surrounding debris.

Paul Lucas (1664 -1737 CE)

The artist, Paul Lucas (1664 Rouen – 1737 Madrid), and antiquary to Louis XIV of France, is one of the earliest sources of information from Upper Egypt, visiting Thebes and the Nile up to the cataracts. In the book in which he subsequently published the account of his travels, he gives us some idea of the state of the remains in his time, but his account is very rambling and unreliable. His drawing is a partial view of the ruins of the alleged labyrinth. Remark the ruins on top of an intact and proportional colossal temple. Lucas states that an old Arab who accompanied his party professed to have explored the interior of the ruins many years before, and to have penetrated into its subterranean passages to a large chamber surrounded by several niches, “like little shops,” whence endless alleys and other rooms branched off. A statement that supports the probability that the labyrinth survived the Ptolemaic en Roman times unaffected. By the time of Lucas’s visit, however, these passages could not be traced, and he concluded that they had become blocked up by debris.

Richard Pococke (1704 – 1765 CE)

The next explorer to visit the spot seems to have been Dr. Richard Pococke. From 1737-40 CE he visited the Near East. Exploring Egypt, Jerusalem, Palestine and Greece. In his book “Description of the East” that appeared in 1743 he wrote; “We observed at a great distance, the temple of the Labyrinth, and being about a league from it, I observed several heaps as of ruins, covered with sand, and many stones all round as if there had been some great building there: they call it the town of Caroon (Bellet Caroon). It seemed to have been of a considerable breadth from east to west, and the buildings extended on each side towards the north to the Lake Moeris and the temple. This without doubt is the spot of the famous Labyrinth which Herodotus says was built by the twelve kings of Egypt.” He describes what he takes to be the pyramid of the labyrinth as a building about 165 feet long by 80 broad, very much ruined, and says it is called the “Castle of Caroon”

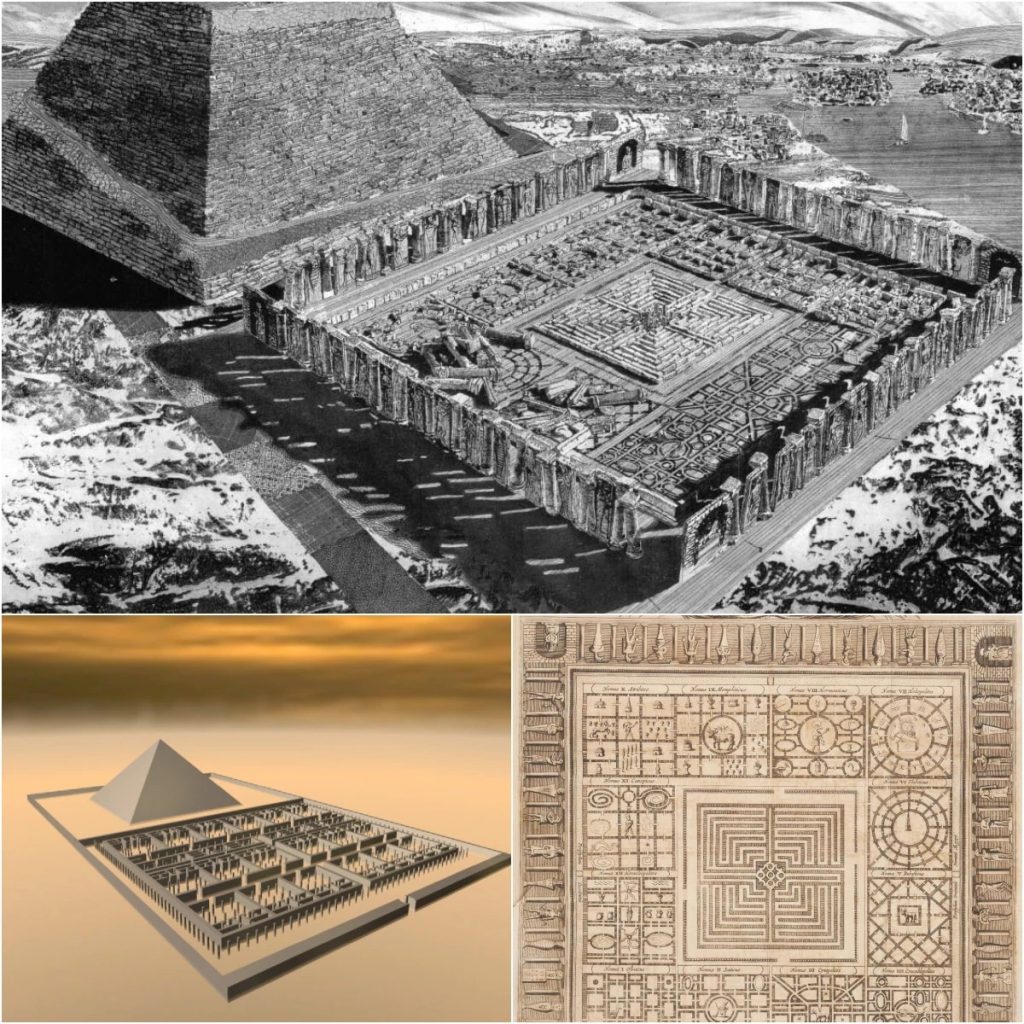

Luigi Canina(1795-1856 CE)

Many attempts have been made to visualize the labyrinth as it existed in the time of Herodotus. The drawing of the Italian architect and archaeologist Luigi Canina(1795-1856) shows, in plan, one such reconstruction. Among Canina’s his works are: some construction at the Villa Borghese and Casino Vagnuzzi outside of Porta del Popolo in Egyptian style. He was professor of architecture at Turin, and his most important works were the excavation of Tusculum in 1829 and of the Appian Way in 1848, the results of which he embodied in a number of works published in a costly form by his patroness, the queen of Sardinia. Canina is also noted for his studies of history and archeology: Ancient architecture described and represented in documents (1830-44).

previous expeditions

At the beginning of the 19th century Hawara was studied by Napoleon Bonaparte’s famous expedition in Egypt. The French expedition (1799-1801) described the Hawara pyramid, and the pharaonic temple south of it. The remains in the north and the west were wrongly identified as the labyrinth (Jomard-Caristie 31 December 1800) by Jomard who believed that he had discovered the ruins of the labyrinth.

The first excavations at the site were made by Karl Lepsius, in 1843. Lepsius was commissioned by King Frederich Wilhelm IV of Prussia to lead an expedition to explore and record the remains of the ancient Egyptian civilization. The Prussian expedition was modeled after the earlier Napoléonic mission, and consisted of surveyors, draftsmen, and other specialists. In Hawara K. R. Lepsius, carried out considerable excavations in the cemetery to the north and on the northern and south-eastern sides of the pyramid and in the area of the labyrinth and claimed to have established the actual site of the labyrinth (Lepsius 1849), attaching great importance to a series of brick chambers which they unearthed. The data furnished by this party, however, were not altogether of a convincing character, and it was felt that further evidence was required before their conclusions could be accepted. Lepsius thought that the structures excavated by his team were parts of the temple of King Amenemhat III, but later research showed that they belonged to Roman tombs. Since the expedition of Lepsius, the place came to be known as a findspot for some high quality royal statues.

The pupil of Lepsius, G. M. Ebers, who did much to popularise the study of Egyptology by a series of novels, said that if one climbed the pyramid hard by, one could see that the ruins of the Labyrinth had a horseshoe shape, but that was all.

In 1882 the Italian Luigi Vassalli (1855-1899) started his excavations in the area near the pyramid of Hawara, after having surveyed the site. Vassalli searched in vain for the pyramid’s entrance. He also excavated across the Bahr Wahbi, in the village east and south of the labyrinth and in the necropolis to the north of the pyramid (Vassalli 1867, pp.62-65; Vassali 1885).

The pioneer of systematic methodology in archaeology, Sir William Matthew Flinders Petrie undertook the first large-scale excavations at Hawara in 1888-1889 and 1910-1911. He revealed attestations of human occupation and activity dating back from the Middle Kingdom to Coptic times. The first object of Petrie’s archaeological work at Hawara was the study of the Middle Kingdom pyramid. On the second place he was interested in the labyrinth of the literary sources. Moreover he extended his activity area towards the area north of the pyramid where he discovered a huge cemetery. The most famous finds revealed by Petrie at the Hawara necropolis are the gilded masks and mummy portraits, which he found in the late-Ptolemaïc and Roman tombs, e.g. the wooden panel of Hermione, the schoolteacher, being among the very few surviving examples of painted portraits from Classical Antiquity, the “Faiyum portraits”. In 1888 he first focused on the pyramid and the labyrinth. He divided the necropolis north of the pyramid in chronological zones ranging from the Middle Kingdom to Byzantine times. Here he found the first Roman mummy portraits and masks. In 1889 he identified the pyramid as that of the 12th dynasty pharaoh Amenemhat III and his daughter Neferuptah. He continued working in the burial area in the northern part of the site and cleared a Byzantine basilica north-west of the pyramid. His successful campaigns attracted other excavators, in search of papyri and mummy portraits.

The actual site of the Egyptian labyrinth was most important, finally identified by Professor Flinders Petrie in 1888. Sufficient of the original foundations remained to enable the size and orientation of the building to be roughly determined. Namely about 304 meters [997 feet] long and 244 meters [800 feet] wide. Large enough to hold the great temples of Karnak and Luxor. He found that the brick chambers which Lepsius took to be part of the labyrinth, were only remains of the Roman town built by its supposed destroyers. He concluded that the labyrinth itself being so thoroughly demolished that only the great bed of fragments remained on top of an artificial stone foundation. Anyway Petrie drew up a tentative restoration based upon the descriptions of Herodotus and Strabo so far as these tallied with the scanty remains discovered by him. He speculated that the shrines which he found formed part of a series of nine, ranged along the foot of the pyramid, each attached to a columned court, the whole series of courts opening opposite a series of twenty-seven columns arranged down the length of a great hall running east and west; on the other side of this hall would be another series of columned courts, six in number and larger than the others, separated by another long hall from a further series of six.

His finding at Hawara included also scattered bits of foundations, a great well, two door jambs, one to the north and one to the south, two granite shrines and part of another, several fragments of statues and a large granite seated figure of the king, who is still generally recognised to have been the builder of the labyrinth. Namely Amenemhet (or Amenemhat) III of the XIIth Dynasty (also known as Lampares), who reigned twenty-three centuries BCE.

W.M. Flinders Petrie wrote (Ten Years Digging in Egypt, pp. 91-92): “Though the pyramid was the main object at Hawara, it was but a lesser part of my work there. On the south of the pyramid lay a wide mass of chips and fragments of building, which had long generally been identified with the celebrated labyrinth. Doubts, however, existed, mainly owing to Lepsius having considered the brick buildings on the site to have been part of the labyrinth. When I began to excavate the result was soon plain, that the brick chambers were built on the top of the ruins of a great stone structure; and hence they were only the houses of a village, as they had at first appeared to me to be. But beneath them, and far away over a vast area, the layers of stone chips were found; and so great was the mass that it was difficult to persuade visitors that the stratum was artificial, and not a natural formation. Beneath all these fragments was a uniform smooth bed of beton or plaster, on which the pavement of the building had been laid: while on the south side, where the canal had cut across the site, it could be seen how the chip stratum, about six feet thick, suddenly ceased, at what had been the limits of the building. No trace of architectural arrangement could be found, to help in identifying this great structure with the labyrinth: but the mere extent of it proved that it was far larger than any temple known in Egypt. All the temples of Karnak, of Luxor, and a few on the western side of Thebes, might be placed together within the vast space of these buildings at Hawara. We know from Pliny and others, how for centuries the labyrinth had been a great quarry for the whole district; andits destruction occupied such a body of masons, that a small town existed there. All this information, and the recorded position of it, agrees so closely with what we can trace, that no doubt can now remain regarding the position of one of the wonders of Egypt.”

In 1911, Petrie returned to Hawara to excavate in the labyrinth and to find more of the so-called Faiyum portraits on the Roman Period mummies. As usual, Petrie published his results soon after his work and also depicted partial reconstructions of the complex within his volumes. These were still mainly based on the classical authors, and only few points depended on the little evidence he found for the original architecture (Petrie et al. 1912). The crucial information Petrie knew ‘from Pliny and others’ about the disappearance of labyrinth as a quarry is unscientificly vague and even completly lost for contemporary researchers. That the whole of the structure of the labyrinth could have been carried away was certainly a possibility, but it would have been a Herculean feat considering its size and the mass of the stones used to build it. If this was indeed the labyrinth described in antiquity, no act of pillaging could match the total annihilation that should have occurred there. During Petrie’s absence at Hawara excavations were subsequently undertaken in 1892 by Heinrich Brugsch, J. von Levetzau and von Niemeyer and Richard Von Kaufmann, who all discovered Roman mummy portraits. In the same year R. von Kaufmann discovered the intact Roman mudbrick chamber of ‘Aline’ (see now Germer, Kischkewitz and Lüning 1993). A local dealer discovered four or five portraits and an unknown number of gilded masks (cf. Drower 1985, p.143).

In 1910, G. Lefèbvre excavated on the site (cf. Parlasca 1966, p.34; Grimm 1974, p.35) and Petrie resumed his work in the Labyrinth and in the Roman cemetery, again finding lots of mummy portraits.

Among other parts of the site the area east of the pyramid was further excavated in more recent times by the Inspectorate of Faiyum Antiquities worked in the necropolis north and east of the pyramid and by the Egyptian archaeologists by Fathi Melek and Hishmat Adib (1972), Motawi Balboush (1974) and el-Khouli (1983). (see the reports in Leclant 1973, p.404; Leclant 1975, p.208-209, and Leclant 1984, p.370) The entrance to the pyramid was cleared by A. Al-Bazidy in 1995.

The last survey before the Mataha-expedition of the site was undertaken in 2000 by a Belgian mission. From 5 to 23 March 2000 the Catholic University of Leuven mapped the architectural remains visible on the surface. The complementary study of the surface pottery resulted in a chronological framework of the different areas of the site and in a representative catalogue of the Hawara ceramics covering the period between the Middle Kingdom (ca. 2000 BCE) and the 10th century CE. Inge Uytterhoeven (field director Hawara 2000 survey) of the Leuven University published the survey report in fall 2009.

total expedition time line

1800 31 December: survey by two engineers of the French expedition, Caristie and Martin, published by Jomard in “Description de l’Egypte, Antiquités, volume IV (Pancoucke edition, Paris1821), 478-485 Comment: valuable as the first scientific survey, carried out earlier than the cutting of the Bahr Wahbi canal across the site.

1818 Labyrinth Field examination by Giovanni Battista Belzoni, as decribed in his book: “Narrative of the Operations and Recent discoveries within the pyramids, temples,tombs and excavations in Egypt and Nubia; and a journey to the coast of the Red Sea, in search of ancient Berenice; and another in the oasis of Jupiter Ammon (1820). After Belzoni’s early death in 1823, Sarah Banne his wife and travel companion still lived for many years in Brussels (Belgium).

1820s: date uncertain: survey by John Gardner Wilkinson, published in his “Modern Egypt and Thebes, being a description of Egypt, including the information required for travellers in that country, volume II (London, 1843), 337-340

1830 – 1835: Linant de Bellefonds. The canal construction of the Bahr Wahbi by the French engineer Linant de Bellefonds, is normally not classified as an archaeologic expedition, but it certainly needs consideration. Seen the archaeological interests of the French engineer and the higher elevation of the pyramid base, we can presume that Linant de Bellefonds intentionally directed the canal towards the pyramid, in order to cross the labyrinth area. The digging of the canal, as a giant archaeological cross section, surely must have unearthed many antiquities. Per contra, Petrie’s alleged labyrinth foundation remained untouched, like the canal does not reach the according depth.

1837: survey by Howard Vyse and Perring, published in their “Operations carried on at the Pyramids of Gizeh in 1837, volume III (London, 1842), 82- 83 Comment: first record of the present canal across the site

1840s: survey and excavation by the expedition under Richard Lepsius, published in his “Denkmaeler aus Aegypten und Aethiopen I (Berlin, 1849), plates 46-49, with posthumous publication of his notes in “Denkmaeler Text II (Berlin, 1904), 11-30 Comment: this is the most accurate published account of the site, from a time when the ruins of the Hellenistic and Roman village survived over the area of the Labyrinth. (Lepsius interpreted those ruins as part of the original complex.)

1862 August: excavations around the site by Luigi Vassalli, published in the journal “Recueil de Travaux 6 (1885), 37-41

1888-1889: excavations and survey by William Matthew Flinders Petrie, published in his reports “Hawara, Biahmu and Arsinoe” (London,1889) and “Kahun, Gurob and Hawara” (London, 1890): his letters home are now in the Griffith Institute, Oxford (the ‘Petrie Journals’), and his pocket books (the ‘Petrie Notebooks’) are in the Petrie Museum (published with Secure Data Services in the Petrie Museum Archives CD-ROM, 1999) Comment: the main achievement of Petrie lies in his survey of the pyramid and its inner chambers, and in his discovery and rescue of the famous encaustic mummy portraits from the Roman Period burials north of the pyramid. In other areas the quality of his work falls below modern standards, reflecting the early date in the history of archaeology and in his own career. His survey of the area around the pyramid is inadequately recorded, and most of the tombs were emptied by workmen without Petrie himself ever seeing the finds in place. 1892: exploration of the Roman Period cemeteries at Hawara by R. v. Kaufmann, mentioned as the discoverer of a group burial containing eight mummies, in “Renate Germer, Das Geheimnis der Mumien, Ewiges Leben am Nil (Berlin 1998), 150-151

1911: excavation of the labyrinth area and the Hellenistic and Roman Period cemeteries by William Matthew Flinders Petrie, published in his “The Labyrinth, Gerzeh and Mazghuneh (London 1912), and “Roman Portraits and Memphis IV” (London 1911) Comment: in this season Petrie uncovered some of the most remarkable sculpture fragments, as well as more structures within the area of the labyrinth.

1973 Fathi Melek and Hishmat Adib excavated 1972 some shaft tombs of the Middle and New Kingdom (Orientalia 42 (1973), 404)

In June 1974 excavated a mission of the Service des Antiquités under the direction of Motawi Balboush in the east of the pyramid from Hawara. They found the undisturbed tomb of a certain “Kheif Maakht”. The tomb is not yet published, cf. Orientalia 44 (1975), 208-9

1984 Ali el-Khouli excavated 1983 about 20 tombs of the New Kingdom, Orientalia 53 (1984), 370

2000 Belgian survey “the Hawara 2000 surface-survey of the Faiyum Project” (Netherlands-Flemish Institute in Cairo) (Katholieke Universiteit Leuven – Section: Ancient History). – Willy Clarysse (General director) – Inge Uytterhoeven (Field director) – Anny Cottry (Photographer) – Katrien Cousserier (Archaeologist) – Bart Demarsin (Archaeologist) – Lieven Loots (Archaeologist) – Sylvie Marchand (Pottery specialist – IFAO) – Veerle Muyldermans (Archaeologist) – Ilona Regulski (Egyptologist) – Katrien Slechten (Archaeologist) > – Ayman Mohammad Sedik el-Hakim (Inspector) – Ashraf Sobhy Rezkalla (Inspector)

21 april 2004 Groundwater examination of Hawara, by Keatings, K.; Tassie, G.J.; Flower, R.J.; Hassan, F.A.; Hamdan, M.A.R.; Hughes, M.; Arrowsmith, Carol. Published in Geoarchaeology magazine, volume 22 (n°5) 2007 Wiley interscience

2008 February-March Mataha-expedition: Egyptian-Belgian geophysic research of the Hawara Necropolis (Pyramid + Labyrinth) by the National Research Institute of Astronomy and Geophysics and Ghent University. The General Director of the NRIAG Geophysic Survey was Associate Prof. dr. Abbas Mohamed Abbas (National Research Institute of Astronomy & Geophysics and Member of the Egyptian Committee of the Protection of Antiquities from Environmental Effects).

March 2008 survey of the Hawara pyramid (Cairo University – Wroclaw University). General Director Prof. Dr. Alaaeldin Shaheen, Dean of the Faculty of Archaeology of Cairo University.

April 2009 renovation & excavation works Hawara Necropolis by the Cairo University – Wroclaw University cooperation, directed by Prof. Dr. Alaaeldin Shaheen (UCairo). The Egyptian Polish mission is shortly after the UCairo Labyrinth Conference (1-3 april 2009 ) suspended by the Supreme Council of Antiquities.

labyrinth bibliography

Arnold, D., Das Labyrinth und seine Vorbilder, Mitteilungen des Deutschen archäologischen Institus Kairo 35 (1979), 1-9

Arnold, D., Lexikon der Ägyptologie, entry: Labyrinth, 905-907

Blom-Boer, I., Sculpture Fragments and Relief Fragments from the Labyrinth at Hawara in the Rijksmuseum van Oudheden, Leiden, OMRO 69 (1989), 25-50. Rijksmuseum van Oudheden, Leiden, OMRO 69 (1989), 25-50

Lepsius, R., Denkmäler, I, 46-48, Berlin 1897

Lepsius, R., Denkmäler, Textband II, 11-30, Berlin 1849

Lloyd, A.B., The Egyptian Labyrinth, Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 56 (1970), 81-100

Michalowski, K. The Labyrinth Enigma: Archaeological Suggestions, Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 54 (1968), 219-222

Obsomer, C. in: Amosiadès (Mélanges offert au professur Claude Vandersleyen par anciens étudiants, Louvain-la-Neuve 1992), 221-324 Petrie, W.M.F., Hawara, Biahmu and Arsinoe, London 1889

Petrie, W.M.F., Kahun, Gurob, and Hawara, London 1890

Petrie, W.M.F., Wainwright, G.A. and Mackay, E., The Labyrinth, Gerzeh and Mazghuneh, (British School of Archaeology in Egypt and Egyptian Research Account, 18th Year) London 1912

Uphill, E.P., Pharaoh ́s Gateway to Eternity, The Hawara Labyrinth of King Amenemhat III, Paul International, London 2000

O. Kimball Armayor, Herodotus’ Autopsy of the Fayoum: Lake Moeris and the Labyrinth of Egypt (Gieben, Amsterdam 1985).

Geryl P., The Orion Prophecy, Adventures Unlimited Press 2002

Herman Kern, Through the Labyrinth; Designs and Meanings over 5,000 Years, Prestel 1982

W.H.Matthews, Mazes & Labyrinths: Their History & Development, Dover Publications, New York 1970

Joyce Tyldesley, Egypt: How a Lost Civilisation Was Rediscovered, BBC Books 2007

Albert Slosman, L’Astronomie selon les Egyptiens, Laffont Paris 1983

Kevin Keatings & co, An Examination of Groundwater within the Hawara Pyramid, Egypt

Geoarchaeology magazine, volume 22 (n°5) 2007 Wiley interscience

Colin Renfrew, figuring it out, The parallel visions of artists and archaeologists, Thames & Hudson 2003

Inge Uytterhoeven, Hawara in the Graeco-Roman Period: Life and Death in a Fayum Village, Peeters, Leuven 2009

Additional Source Documents:

Contact Louis De Cordier: https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=100008150646147

Contact Bill Brown: https://www.facebook.com/PuramisInternational

Contact Trevor Grassi: trevor@archaeologicalrescue.org

or: https://www.facebook.com/Gizatology

Contact ARF: info@archaeologicalrescue.org

Louis De Cordier, official Labyrinth of Egypt facebook group: https://www.facebook.com/labyrinthofegypt

Labyrinth of Egypt on X: https://x.com/labofEgypt

Labyrinth of Egypt Substack, by Louis De Cordier: https://labyrinthofegypt.substack.com/

The Secret Underworld of Giza: The Lion and the Labyrinth (William Brown and Trevor Grassi): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=O6o77G5Najg&list=PL5YUkAb_nbNTse2hkEDOxIqNbYKq2UAVw&index=2

HAWARA RISING (Louis De Cordier, William Brown, Trevor Grassi: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Gm70-UBqY_g&t=5937s

REMOTE VIEWING HAWARA, Tony Rodrigues, Vicki Burke, Trevor Grassi: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ee5oIqHARbc

Original Mataha Expedition video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=k4UiiBTzXRY

Pyramid Code, Dr. Carmen Boulter: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=v7z6rj5S538

UnchartedX/Ben Van Kerkwyk on Hawara: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xwK3XIxTvzU

GeoScan Systems: https://www.geoscansystems.de/

GeoScan Systems Slideshow: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1FGfHNL2JlcLHRSkmg5eYrtuYnAi6FAs9/view?fbclid=IwY2xjawJkUKRleHRuA2FlbQIxMQABHsKlbwDve2oskmkcwAxqh3zycdp8OlVD_pckFmZ_b8TRslOxcoMO_7ypObzB_aem_rNtUBCS0_e1Yc5uaFhkDXw

MerlinBurrows: https://www.merlinburrows.com/

Polish report on Hawara, University of Wroclaw: https://wisdomofnations.com/egypt/hawara/hawara-research-2008-2009-report/

Additional report from Wroclaw University: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/292139616_GPR_research_around_the_Hawara_pyramid_Fayum_Egypt

Mataha Expedition report, Hawara: https://drive.usercontent.google.com/u/0/uc?id=1YqntaYOhvSWA7fd3jFYToPqx34odntjB&export=download

[NRIAG] National Research Institute of Astronomy and Geophysics, Geophysical Studies of Hawara Pyramid Area – Faiyum: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1jxEKQOXKc_vuJwgAcyzr4SwYJCvZ5NCF/view

Dr. Abbas, NRIAG report on Hawara: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/277389608_VLF-EM_study_for_archaeological_investigation_of_the_labyrinth_mortuary_temple_complex_at_Hawara_area_Egypt

Dr. Abbas, Mapping of subsoil water level and its impacts on Hawara archeological site by transient and multi-frequency electromagnetic survey: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/289641089_Mapping_of_subsoil_water_level_and_its_impacts_on_hawara_archeological_site_by_transient_and_multi-frequency_electromagnetic_survey

Mark Carlotto Report on Hawara: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/374151908_Space-Based_Ground_Penetrating_Imaging_of_the_Ancient_Labyrinth_at_Hawara

Article 2 (Mark Carlotto): https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4518835&fbclid=IwY2xjawK_05xleHRuA2FlbQIxMABicmlkETF2M0FsR1dZcDA2NGRMUTgzAR6nQNIKUcCNScA_3vvLu9wyqUUXDXxFamYN5WA2d44qloy5iF77cASBjMQCbQ_aem_xlKm52Wdz6JVDruEXFaMKQ